Afghanistan’s Bitter Future

A version of this this article was first published on The Globalist on December 27, 2014

The consequences of the lengthy failure of the United States to address Afghan corruption.

The United States has spent $104 billion on reconstruction in Afghanistan over the last 13 years. Approximately $62 billion of this total has been used to support the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF). Nobody knows how much of this U.S. taxpayer cash has been stolen. Nobody seems to be confident that the U.S.-funded programs can be sustained as the U.S. winds-down its Afghan engagement.

At the end of 2014 – in a few days’ time – U.S. combat operations in Afghanistan will officially end. John F. Sopko, Special U.S. Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), recently noted that more than 10,000 U.S. military personnel will remain, but in a training and support role. He is worried that, despite the vast aid provided by the U.S. to help Afghanistan build a democratic and secure nation, the massive effort will unravel.

U.S. official actions have often added to the corruption problem in Afghanistan. Too frequently, USAID, State Department, military and intelligence officials have paid Afghan officials and businessmen handsomely for all manner of favors, splashing cash around and infrequently auditing such outlays. These conclusions are drawn from a series of reports by SIGAR, most one on “High-Risks” in mid-December 2014, together with a landmark report by the Department of Defense earlier this year. These reports highlight the waste, inefficiency and corruption in U.S. programs in Afghanistan and the failure of our military leaders to understand adequately the corruption issue in Afghanistan.

A costly affair

It will cost the Afghan government billions of dollars annually to maintain its army and police force, to finance essential energy infrastructure, to run the key governmental departments, and to continue many of the projects funded by the U.S. and other Western countries. Sopko states that total government revenues amount to just about $2 billion a year – far, far less than is essential. Vast amounts of foreign aid will have to be raised for years to come to keep ANSF and the government going.

I asked Sopko how much of the $104 billion in reconstruction funds has gone missing and where has it gone? He replied: “It is impossible to provide an exact figure. The total runs into billions and billions. There is not even a database that has tracked all the contracts that have been concluded even though we have been in the country for 13 years – this is horrible. It is every Afghan’s dream to get this money out of the country. We just cannot lose this amount of money again, the American people will not stand for it.”

Afghans have long been worried about corruption at every governmental level in the country, but not until recently have top U.S. foreign and defense policy officials taken it seriously. They have always placed the goal of stability in Afghanistan above all other issues. They have long refused to accept, and many of the leaders of the U.S. foreign policy establishment still refuse to accept, that in countries like Afghanistan and Iraq there can be no sustainable stability without accountable and transparent governance.

This is not a matter of options. The notion, so long dominant at the Pentagon and the National Security Council that you have to have order and stability first, then you can work on corruption and good governance, has contributed to Afghanistan’s bleak prospects today. Building good governance has to be fully imbedded into security and stability programs – this a critical lesson to be drawn from the massive U.S. engagement in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

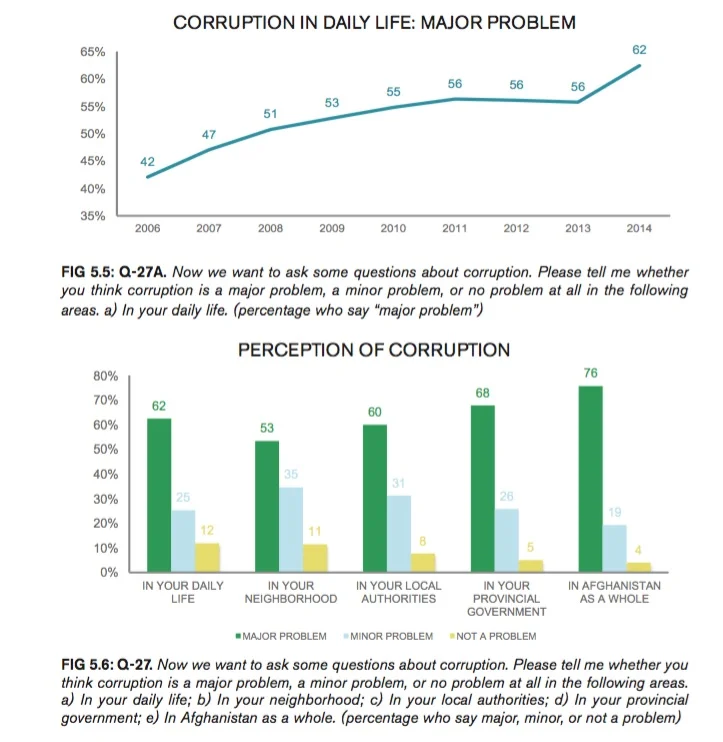

The perceptions of Afghans about corruption are clearly evident in the findings of the 2014 Asia Foundation Annual Survey from which the charts below are taken -

No transparency, no stability

Confidence in the outlook might be greater if it was not for two startling situations: the first is the catastrophic example of what has happened to the military in Iraq; and, the second is the depressing catalogue of abuse to be found in the regular reports published by Sopko’s office.

On the first point, the U.S. spent approximately $25 billion building the military in Iraq and then when ISIS invaded Mosul last June, the Iraqi soldiers ran away. Their generals had stolen funds meant to have been paid to the rank and file, while American military equipment had been sold off with the proceeds pocketed by officers and their cronies. Could the same happen in Afghanistan? Sopko is not about to give a negative answer, but he is worried.

And then, secondly, there is the enormous toll taken in Afghanistan by the combination of waste, inefficiency and corruption that has characterized so much of the U.S.-funded program. For example, SIGAR’s “High-Risk” report noted an examination in 2013 of $4.7 billion in planned and ongoing military construction projects. It concluded that the U.S. Department of Defense is funding a program that is “potentially building permanent facilities in excess of eventual needs, and is doing so without knowledge of current facilities’ utilization or the Afghan government’s willingness or ability to sustain them.”

To take another example, SIGAR said it reviewed a U.S. funded program to provide literacy training in the Afghan army. It concluded that, “despite a $200 million military literacy-training contract, no one appeared to know the overall illiteracy rate of the ANSF…there was no ability to measure the effectiveness of the literacy training program and determine the extent to which overall literacy of the ANSF has improved.”

Sopko is concerned that the full scale of the potential vulnerabilities to U.S.-funded reconstruction programs in Afghanistan is inadequately appreciated. As a result, he has published the new “High-Risks” report that places “Corruption/Rule of Law” as the number one concern. His worries are well placed, because he is the not the first to consistently draw attention to inadequate auditing of U.S. reconstruction programs, low-quality management of military support programs, and grossly insufficient sensitivity by senior U.S. officials, including generals, to corruption issues.

The lesson of Iraq

In a book that I wrote in 2012, “Waging War on Corruption – Inside the Movement Fighting the Abuse of Power,” I highlighted the risks of failure of U.S. objectives in Afghanistan because the lessons from Iraq were being ignored. The scale of corruption in Iraq is and was enormous and a matter of deep concern to then Special U.S. Inspector General for Iraq, Stuart Bowen. I quoted him extensively in my book on his experiences. In his final report, “Learning From Iraq,” Bowen highlighted a detailed set of recommendations to the Department of Defense in particular to closely monitor all U.S. spending, to evaluate programs in terms of corruption, waste and inefficiency, and to halt programs that went off the rails. The U.S. military in Iraq, and then in Afghanistan, ignored those recommendations.

Sopko is not the first to draw attention to inadequate auditing of U.S. reconstruction programs. But Sopko is the first to say that corruption in Afghanistan is a topic to which the U.S. State Department and Department of Defense officials, alongside the military, assigned a low priority for far too long. It is cold comfort for Sopko to note today that gradually U.S. military leaders are coming to understand how costly their approaches have been, not just in terms of U.S. funds that have been stolen, but also with regard to the sustainability of the civil and military programs that the U.S., has directed in Afghanistan.

It has taken too many years for U.S. military leaders to come to understand how costly their approaches have been. A Department of Defense analysis published earlier this year, in response to a call in March 2013 by General Dunford, the commander of U.S. and allied forces in Afghanistan, examined counter/anti-corruption (CAC) operational challenges. The Joint and Coalition Operational Analysis, a division of the Department of Defense, concluded with two key findings:

- The United States’ initial support of warlords, reliance on logistics contracting and the deluge of military and aid spending overwhelmed the absorptive capacity of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GIRoA)

Those acts also created an environment that fostered corruption and impeded later counter/anti-corruption (CAC) efforts.

The necessary preconditions for combating corruption did not exist. This was due to a delayed understanding of the nature of Afghan corruption, decreasing levels of physical security, lack of political will on the part of both the international community and GIRoA, and lack of effective popular pressure against corruption. All of that resulted in a large-scale culture of impunity that frustrated CAC efforts. One of the critical issues to watch in any country’s reconstruction is the application and development of the rule of law. The Commander, International Security Assistance Force (COMISAF) guidance, in concert with the efforts of key CAC-related task forces, improved understanding of the corruption issues and supported intelligence-driven CAC planning and operations. However, lack of unity of effort reduced the effectiveness of CAC operations, and the persistent lack of political will on the part of GIRoA rendered almost all counter-corruption efforts moot.

One of the critical issues to watch relates to the rule of law. Afghans have long seen the judiciary as corrupt. They understand that a system of impunity exists that gives so many powerful Afghans a sense that they are above the law. It is impunity that also enables criminals operating the heroine trade, often in league with corrupt public officials, to pursue their crimes, just as it the prevailing impunity that makes life easy for the business people in the country who organize the vast money-laundering system that sends stolen funds out of the country and into foreign bank accounts, including billions from American taxpayers.

A key question today is whether the new government of Afghanistan, alongside our military leaders with their fresh understanding of the importance of the corruption issue, are too late to change Afghanistan’s course. Tackling impunity will be a formidable challenge. So too will securing foreign aid donor confidence so that more billions of dollars keep flowing into the Afghan national budget. Afghanistan, after all, according to the 2014 Transparency International Corruption Perception Index, continues to be ranked among the handful of most corrupt countries in the world.